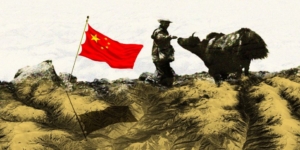

China Is Using Tibetans as Agents of Empire in the Himalayas

In April 1998, with the Himalayan passes still more than 6 feet deep in snow, Penpa Tsering, a 22-year-old Tibetan herder, set off to the south from his home in Tibet across a remote 15,700-foot-high pass called the Namgung La. He was leading a train of a dozen yaks carrying tsampa (parched barley flour), rice, and fodder.

Penpa Tsering had been dispatched by the village leader of Lagyab, a settlement in Lhodrak county nearly 7 miles northeast of the Namgung La as the crow flies, to take desperately needed supplies to four other Tibetan herders who were spending the winter in a remote grassland area at 14,200 feet on the south side of the pass. Without the food that Penpa Tsering’s yaks were carrying, the herders would not survive the winter. After one day and one night of walking, Penpa Tsering reached his fellow herders and saved their lives. They later said they had expected to die. But Penpa Tsering never made it back to Lagyab: He died in an avalanche as he tried to find his way back across the pass.

About this project: Robert Barnett, Matthew Akester, Ronald Schwartz, and two Tibetan researchers who asked to remain anonymous conducted the research for this story using material drawn from official Chinese media reports, blogs, and newspapers. This story was produced as part of an ongoing collaborative research project into policy developments on Tibet. Nathan Ruser provided additional fact-checking. Note: Place names are given according to usage in Bhutan, where known, or are taken from Tibetan translations of Chinese reports, which may be unreliable.

Read Part 1: China Is Building Entire Villages in Another Country’s Territory

In the Chinese media reports on which this account is based, Penpa Tsering’s death is presented as an act of martyrdom, a minor figure in the pantheon of China’s model citizens. His sacrifice, however, was unnecessary. The men he saved were overwintering in the high pasturelands not to improve their lives or to help their flocks but as pawns in an imperial project designed and driven by politicians in Beijing, 1,600 miles away. Today, that project has expanded into a vast network of quasi-militarized settlements along—and sometimes across—China’s Himalayan borders. Its purpose is to strengthen China’s geopolitical position in the region; it has little or nothing to do with the welfare or interests of the herders. But it cannot function without them.

No nomad freely overwinters in a tent at more than 14,000 feet on the south side of the eastern Himalayas, where storms and snowfall are especially dangerous and access is impossible for six months of the year. Normally, the four men on the south side of the pass would have returned months earlier to the shelter of their families and homes in Lagyab, only a 29-mile walk away and 2,300 feet lower in altitude, long before winter had set in. But someone in the Chinese bureaucracy had decided for reasons that seem obvious, but in fact are not, that the site of the nomad’s camp was “very important and someone needs to be stationed there all year-round.”

The reason for that decision lay in a new territorial claim by China. As Foreign Policy detailed in Part 1 of this investigation, the Namgung La marks the traditional border between Tibet and Bhutan. Thirty years after China annexed Tibet in the 1950s, Beijing changed its view of that border and declared that a 232-square-mile area of northern Bhutan, lying to the south of the Namgung La, had once belonged to Tibet and therefore was now part of China. That area was the Beyul Khenpajong, a remote and uninhabited region, famous throughout the Himalayas as a “hidden valley,” that is exceptionally sacred to the Bhutanese.

China’s claim was based on a 200-year-old document that described a Tibetan monastery called Lhalung as having grazing rights in the Beyul. However, cross-border grazing has been a normal practice in the Himalayas for centuries, with herders from neighboring countries often sharing summer pastures without any implications regarding state sovereignty and, in this case, apparently without conflict in the past. But any hope of cross-border harmony among herders in the Beyul ended on Sept. 30, 1995, when four nomads, together with 62 yaks, were sent over the Namgung La to settle the area permanently. Their mission was to deter Bhutanese herders from grazing their flocks in the area and through their presence to assert China’s claim to the territory.