- ارتباط مستقیم با انجمن

- info@ircfa.com

وزیر امور خارجه کشورمان در پیامی توئیتری بهمناسبت روز ملی چین تاکید کرد

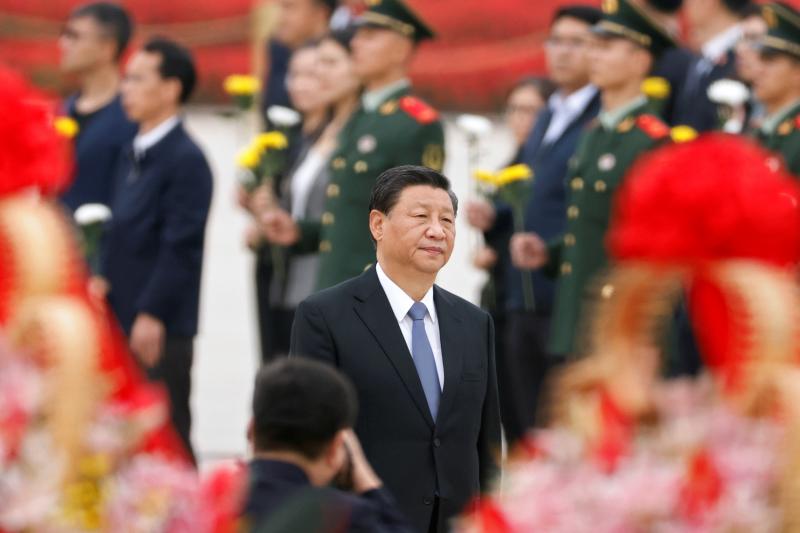

2021-10-02رئیس جمهور روز ملی جمهوری خلق چین را تبریک گفت

2021-10-04The End of China’s Rise

Beijing Is Running Out of Time to Remake the World

The prevailing consensus, in Washington and overseas, is that China is surging past the United States. “If we don’t get moving,” President Joe Biden has said, “they’re going to eat our lunch.” Countries everywhere are preparing, in the words of an Asian diplomat, for China to be “number one.”

Plenty of evidence supports this view. China’s GDP has risen 40-fold since 1978. China boasts the world’s largest financial reserves, trade surplus, economy measured by purchasing power parity, and navy measured by number of ships. While the United States reels from a shambolic exit from Afghanistan, China is moving aggressively to forge a Sinocentric Asia and replace Washington atop the global hierarchy.

But if Beijing looks to be in a hurry, that’s because its rise is almost over. China’s multidecade ascent was aided by strong tailwinds that have now become headwinds. China’s government is concealing a serious economic slowdown and sliding back into brittle totalitarianism. The country is suffering severe resource scarcity and faces the worst peacetime demographic collapse in history. Not least, China is losing access to the welcoming world that enabled its advance.

Welcome to the age of “peak China.” Beijing is a strong revisionist power that wants to remake the world, but its time to do so is already running out. This realization should not inspire complacency in Washington—just the opposite. Once-rising powers frequently become aggressive when their fortunes fade and their enemies multiply. China is tracing an arc that often ends in tragedy: a dizzying rise followed by the specter of a hard fall.

Making a Miracle

China has been rising for so long that many observers think its ascendance is inevitable. In fact, the past few decades of peace and prosperity are a historical anomaly, caused by several fleeting trends.

To start, China enjoyed a mostly safe geopolitical environment and friendly relations with the United States. For most of its modern history, China’s vulnerable location at the hinge of Eurasia and the Pacific had condemned it to conflict and hardship. From the First Opium War in 1839 until the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, imperialist powers ripped apart the country. After China unified under communist rule in 1949, it faced extreme U.S. hostility; Beijing suffered the enmity of both superpowers after the Sino-Soviet alliance collapsed in the 1960s. Isolated and surrounded, China was racked by poverty and strife.

The opening to the United States in 1971 broke this pattern. Beijing suddenly had a superpower ally. Washington warned Moscow not to attack China and fast-tracked Beijing’s integration with the wider world. By the mid-1970s, China had a safe homeland and access to foreign markets and capital—and the timing was perfect. World trade surged sixfold from 1970 to 2007. China rode the momentum of globalization and became the workshop of the world.

If Beijing looks to be in a hurry, that’s because its rise is almost over.

It could do so because China’s government was largely committed to reform. After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) instituted term limits and other checks on its top leaders. It began to reward technocratic competence and good economic performance. Rural communities were allowed to set up loosely regulated enterprises. Special economic zones expanded across the country and allowed foreign businesses to operate freely. In preparation for joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, Beijing adopted modern legal and tax collection systems. China had the right package of policies to thrive in an open world.

China also had the right kind of population. It experienced the greatest demographic dividend in modern history. In the first decade of this century, it boasted ten working-age adults for every senior citizen. The average is closer to five for most major economies.

That demographic advantage was the fortuitous result of wild policy fluctuations. In the 1950s and 1960s, the CCP encouraged women to have many children to boost a population decimated by warfare and famine. The population surged 80 percent in 30 years. But in the late 1970s, Beijing pumped the brakes, limiting each family to one child. As a result, in the 1990s and in the early years of this century, China had a massive workforce with relatively few seniors or children to care for. No population has ever been better poised for productivity.

China did not need much outside help to supply its citizens with food and water and its industries with most raw materials. Easy access to these resources, plus cheap labor and weak environmental protections, made it an industrial powerhouse.